What we can learn from the lives of the enslaved cooks and chefs of Monticello

Understanding history so that we do not repeat it

Amigos,

I think some of you know that I teach a class at George Washington University called “World on a Plate.” I’ve been doing this class since 2013, it’s a great way to show young people all the ways food impacts our world—sustainability, history, diplomacy, immigration, health, national security, science…everything! For this class, I am joined by the incredible Professor Tara Scully and other university professors, as well as amazing guest speakers like Congressman Jim McGovern, our old Longer Tables friend Dan Giusti, and Diné/Navajo chef Brian Yazzie (more on him in a few weeks!) who teach and share their expertise and their insights.

In the past we’ve also done off-site visits to places like the National Museum of American History and the Folger Shakespeare Library. The students also do 20 hours of community service so it’s a great way for them to be digging into how food plays into all parts of life, and to create a new generation of food fighters.

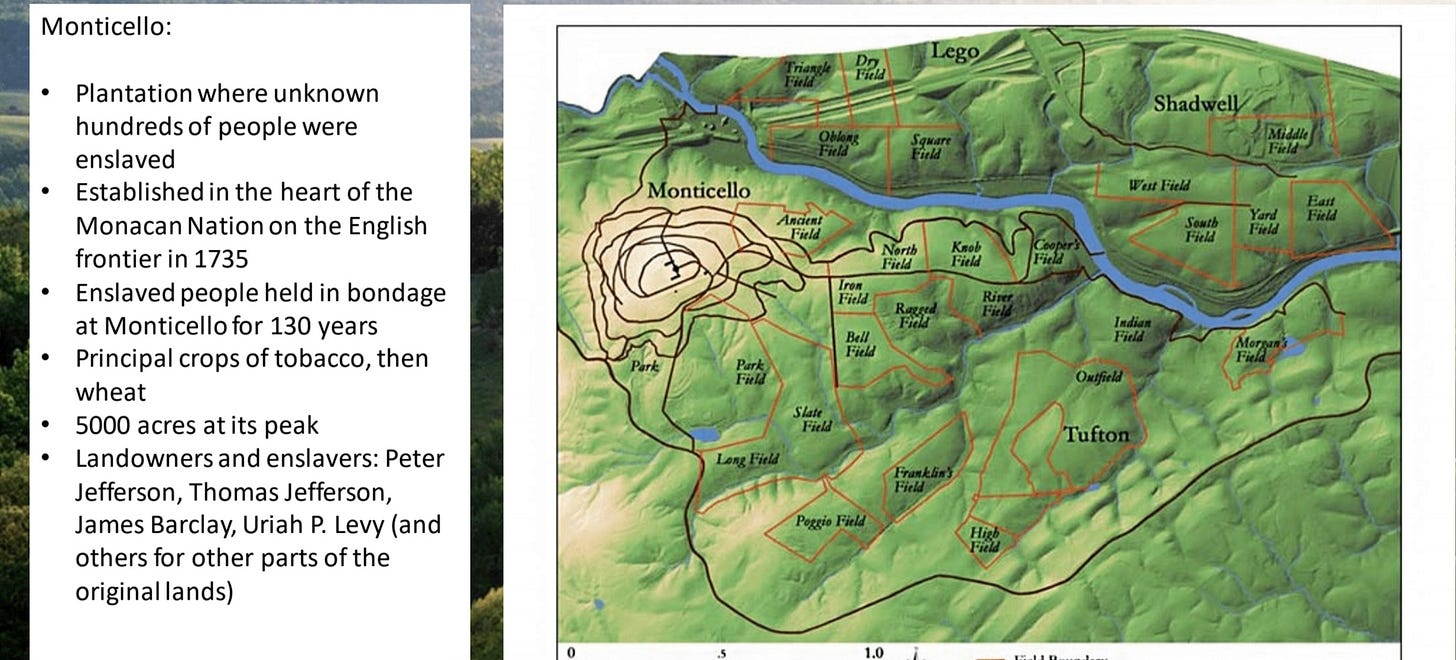

We invited Brandon Dillard, Manager of Historic Interpretation at Monticello Museum built on the plantation home of Thomas Jefferson. Brandon focuses on race, gender, and class constructs in history, and he came to teach a class called “Enslaved People and Modern Southern Foodways.” He focused on Jefferson and the more than 600 enslaved people (the Grangers, the Hemings, and others), who were held in bondage at Monticello for 130 years farming 500 acres of mostly tobacco and wheat.

One of the first things he said to the class was: “Thomas Jefferson was many things: he was the 3rd President of the United States, the author of the American Declaration of Independence, the First Secretary of State, the Second Vice President, an architect, lawyer, diplomat, philosopher, a renowned gourmand and wine enthusiast, and also the enslaver of more than 600 people. Many of them were chefs.”

Brandon talked about so much, but this is something that really hit me: Ursula Granger, who was the first chef of Monticello, was purchased at the request of Jefferson’s wife Martha, along with her husband and two of their sons. Brandon said that Martha would come down to the kitchen with “a cookery book in hand” that she would read to Ursula to teach her how to cook. And she was not just a chef…she was also a wet nurse to Jefferson’s children, did all the washing and ironing, and did meat preservation too. Can you imagine?

Brandon also told us about James Hemings, Sally Hemings’ brother who was sent to Paris to train as a chef and then returned to the US to serve Jefferson, and Wormley Hughes, the first gardener at Monticello who was trained at age 13 under a Scot named Robert Bailey. Wormley was the gardener for all of Jefferson’s life, tending a 1000 square foot vegetable garden with 330 different vegetables, and 1100 fruit trees from all over the world. Someday I would love to help share the stories more widely of James and Sally Hemings, Wormley Hughes, Ursula Granger, and the other enslaved people of Monticello (and people like Hercules Posey, who was enslaved and cooked at Mt Vernon for George Washington!)…these are stories that every American should all be aware of.

The enslaved chefs made dishes like snow eggs, mac and cheese, fried chicken and waffles, and a vegetable soup which was really a gumbo made from indigenous plants like lima beans and patty pan squash and the African plant okra, served over rice. All of these dishes were being cooked by Black chefs, trained in the French method, and enslaved at Monticello.

It is impossible for us to understand how they achieved so much — cooking at the highest level of their day, growing such an amazing range of food — while living an enslaved life that denied their human dignity. The enslaved people who made Monticello the center of culture and civilization in our new country were exceptional in their talents and heroic in their spirit. They achieved all that while being denied the very culture and civilization that Jefferson was known for.

For Brandon, the most challenging piece of Thomas Jefferson is that he was supporting slavery his whole life. Brandon said: “Two hundred years ago, the rights described in the Declaration of Independence did not apply to Native Americans, African Americans, or women. Slavery is the most tangible of these inequalities at Monticello. There have been many suggestions as to why—so many books have been written on the subject, but not one satisfies the glaring immorality that even Jefferson described time and time again. The failure of the Founding Fathers in eradicating the injustice of slavery left a lasting legacy this country continues to struggle with every day.” So true.

My friends, I think each and every one of you, whether you live in DC or anywhere in the world, should go and visit Monticello to learn about these people and their stories from Brandon or the other amazing historians like him. This is the way we start to understand these hard truths that are so important. We have to face them and learn everything we can about the world we live in and America’s very shameful history. I think that only by learning and understanding these truths can we become better than we were and make sure that we do not repeat history again and again and again….

Such important information for us to be aware of, as so much of this history was swept under the rug until recently.

Thank you for sharing this. I know some of this about Monticello as I am a graduate of UVA. I appreciated to learn about the cooking of his enslaved chefs