A young journalist tells a personal story

Sharing the hard truth about teen farmworkers in central California

People of Substack,

Have you heard of Jessica De La Torre? If you haven’t, you have now, and you will continue to hear her name for years to come, I am sure of it.

Jessica (she/they) is a second-year graduate student at Berkeley Journalism, and she was the recipient of a $10,000 fellowship I made to Berkeley Journalism’s 11th Hour Food and Farming Journalism Fellowship in honor of Professor Michael Pollan. Jessica used her fellowship to return this summer to her hometown of Salinas, California, and to devote time writing about teen farmworkers and working on a documentary short produced with her classmate Jennifer Wiley called “Antes del Sol”—which she will share when it is published, and I will send to you all.

The story she wrote this summer was published in Teen Vogue in October; if you have not read it, I hope you will. It’s an amazing and important piece of journalism.

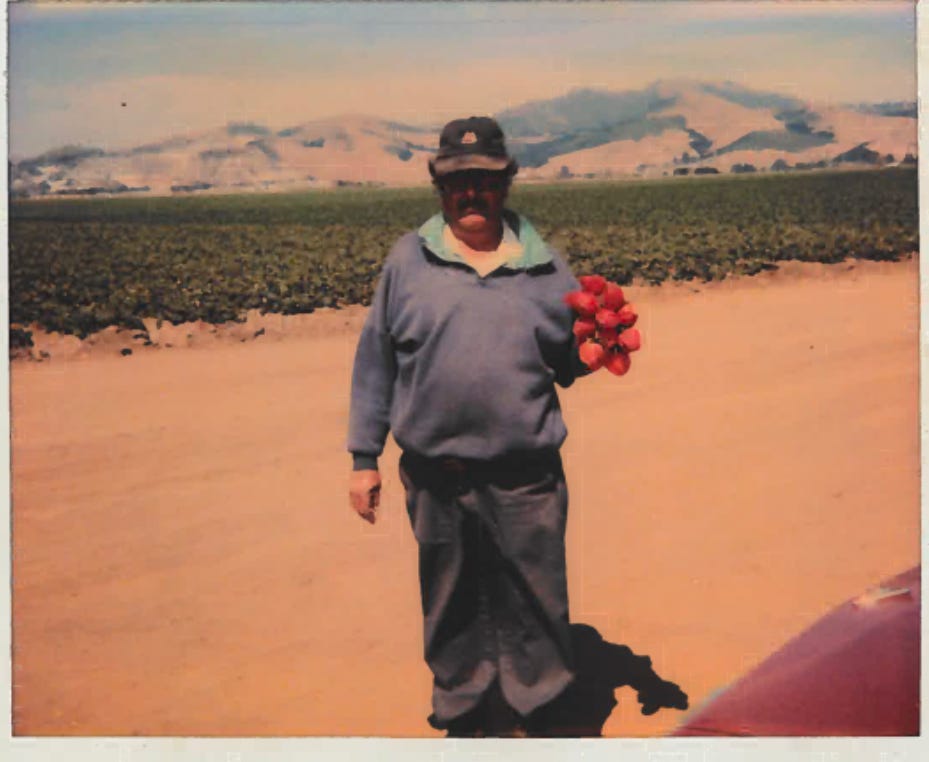

Jessica wrote the story through the eyes of Eva and Mari (not their real names), teens working in the fields of Central California picking strawberries and raspberries. She talks about how the agricultural industry relies on the labor of young people, who are often working with fake IDs (falsely raising their age to legal working age), and missing out on their educations…all to get food from the fields onto our tables.

Jessica points out that the Fair Labor Standards Act has prohibited the employment of children under the age of 16 in most industries since the 1930s, but it doesn’t apply to agriculture. In many states, including California, children as young as 12 can legally work in agriculture when school is not in session. And she says there are as many as 500,000 children from ages 12 to 17 working in American agriculture. A half a million of our kids…is really something.

Jessica’s passion for the issue comes from her own lived experience; she is a first-generation college graduate who grew up in a community where farm work is seen as a right of passage. Her mother worked in the fields alongside her grandfather, who came to the U.S. from Mexico under the Bracero Program. “Teens and even preteens laboring in the fields is so common where I’m from that I never thought of it as child exploitation until I was in college and people were shocked when I mentioned it,” she wrote in Teen Vogue.

After this story came out, I invited Jessica to come to Washington, DC, to talk about it in my class at George Washington University. And then I decided more people need to know about Jessica and her work, so I asked her a few questions for Longer Tables about her childhood, her passion for these issues, and what she hopes she can do to help break teens out of the generational cycle of farmworking.

Tell me a little about your family and childhood.

My family's story is similar to many people in Salinas. My parents are both from Mexico and arrived in the US when they were young and worked in the agriculture industry, one picking produce, and the other packing it in warehouses. They did this in their teens and early adulthood. My twin sister and I are first-generation college graduates who grew up in a community surrounded by fields and known as the salad bowl of the world. Specifically, we were raised on the East Side. I also have a younger sister that just graduated high school.

What inspired you to study journalism?

Journalism has been an outlet that has helped me connect with my community and has empowered the identities I hold as a first-generation Latinx by being able to communicate with people on a deeper level, past the reporter title.

How did you find Eva and Mari, two of the subjects of your story?

Since I used pseudonyms in the story to protect the identities I won’t disclose how I found them. However, youth farm workers can be found in any middle and high schools in agriculture communities across the U.S. These are youth who go unseen in classrooms despite the enormous effort it takes for them to show up to the classroom.

What do you think this story means to them, and to other girls working in the fields?

I think they feel heard and seen. This story represents various generations of youth farm workers that have fed the nation and in return have gone unnoticed and uncelebrated. Being able to share the girls’ stories with thousands of Teen Vogue readers and now to the José Andrés following is a win for my communities’ youth and the generations prior, including my mother and grandmother, that they too matter and should be seen in national outlets without ties to negative stigmas. Their lived realities matter.

What does it mean to you to “break the cycle,” as Eva says?

To break the cycle means to end a generational passage that sometimes is extremely difficult to break from. Sometimes that cycle can be toxic, and it can be lonely. For example, the second teen I wrote about for the Teen Vogue piece, Mari, has tried to break from farm work but it’s been challenging because it’s all she knows and it’s what her family and neighbors do. The pressure of not having resources such as trying to find another job or alternate path like education isn’t just a growing pain as it is for some teens, it’s a shackle.

What do you want the world to know about how food actually gets from our farms to our tables?

Every vegetable and fruit that’s consumed carries a story. The story belongs to those who picked and packaged the produce that winds up in our homes. Leafy greens are packaged by people who are paid poorly, forcing families to live under the poverty line and living in multi-family households. Fruits picked by those who’ve faced sexual harassment on the job and even raped in the fields. Vegetables harvested by people who have dreams past this line of work, heartaches from missing their families for working over time, and health conditions caused by the industry. These realities should be in the foreground of every consumer in the nation. We owe it to our farmworkers to understand this.

What do you hope to achieve with your journalism?

I hope to continue to bring to light stories that people aren’t accustomed to, aware of, and have been overlooked.

This time of year we consumers of information hear a lot about food. On CBS Sunday Morning I learned about the misunderstanding that led to the birth of micro-greens. Today in the Washington Post there was a big story about the incredible job The Netherlands is doing to produce and export food, all while working close to carbon neutral status, and raising meat cruelty free. They are the second largest exporter of food in the world after the USA and the country is the size of Maryland! Fascinating story that filled me with hope. And now, I read about the marginalized US Farmworker, specifically the young people being pulled into the fields by forces greater than themselves. What a wonderful thing you did José by providing a scholarship so that young people like Jessica can strive and reach their goals and then share their worldview with the rest of us, enriching humanity. Bravo to Jessica, and to José. You are making a difference.

A few years ago we drove with our kids from Monterey to San Francisco, and instead of cutting over to the busy 101, we took Highway 1 through the fields up to Santa Cruz. The fields were filled with farmworkers doing back-breaking work, and it was really eye-opening for our kids to see what went into getting food from the fields to our supermarkets and kitchens. Bless those (of all ages) who do this difficult work.